ala StinkyLulu

screenshots from the 20th minute and 7th second of a movie captured using a VLC - your results may differ (different players/timing)

~ You going to the concert tonight?

~ You going to the concert tonight?~ No, I can't... My parents are being bitches this week.

We've Moved. Please visit THEFILMEXPERIENCE.NET

~ You going to the concert tonight?

~ You going to the concert tonight? JA here - I'm sure Nat would want to say something on the death of Ingmar Bergman if he were here, or at least give y'all a chance to say what he meant to you in the comments.

JA here - I'm sure Nat would want to say something on the death of Ingmar Bergman if he were here, or at least give y'all a chance to say what he meant to you in the comments. Yesss. Pewhaps you can. Now take your weapons of mass destruction and get the f*** outta here!

Yesss. Pewhaps you can. Now take your weapons of mass destruction and get the f*** outta here!

[i'm on vacation so a prerecorded note on today's blog event...]

[i'm on vacation so a prerecorded note on today's blog event...] No, it isn't. This is Naomi Finsecker, her mother! Who is this?!

No, it isn't. This is Naomi Finsecker, her mother! Who is this?!

I'm not on a major recuperation mission here; Love Field is not a great movie, and it often can't decide whether to play as a farce, as you might expect from screenwriter Don Roos (The Opposite of Sex, Happy Endings) or as a Serious Drama, as the studio probably preferred and director Jonathan Kaplan, who had recently directed Jodie Foster to an Oscar in The Accused, seems to have wished. Watch the scene where Lurene Hallett (Pfeiffer) regrets to inform fellow bus passenger and cutey patootie Paul Cater (Dennis Haysbert) that she has just mistakenly reported him as a kidnapping suspect to the FBI, and that they'll both hafta skeedaddle out of this Tennessee Greyhound station lightning quick. Roos thinks this is funny, I think, though not without the charged implications of racial profiling and unnecessary roughness. The movie wouldn't work if it were only played for comedy, but where Roos' avalanche of dramatic incidents and tart dialogue cry out for some kind of halfway-screwball approach, Kaplan ladles in lots of portentous night-shots and cheesily ominous music, as though he's been inspired by the hokiest, cheapest aspects of Mississippi Burning.

I'm not on a major recuperation mission here; Love Field is not a great movie, and it often can't decide whether to play as a farce, as you might expect from screenwriter Don Roos (The Opposite of Sex, Happy Endings) or as a Serious Drama, as the studio probably preferred and director Jonathan Kaplan, who had recently directed Jodie Foster to an Oscar in The Accused, seems to have wished. Watch the scene where Lurene Hallett (Pfeiffer) regrets to inform fellow bus passenger and cutey patootie Paul Cater (Dennis Haysbert) that she has just mistakenly reported him as a kidnapping suspect to the FBI, and that they'll both hafta skeedaddle out of this Tennessee Greyhound station lightning quick. Roos thinks this is funny, I think, though not without the charged implications of racial profiling and unnecessary roughness. The movie wouldn't work if it were only played for comedy, but where Roos' avalanche of dramatic incidents and tart dialogue cry out for some kind of halfway-screwball approach, Kaplan ladles in lots of portentous night-shots and cheesily ominous music, as though he's been inspired by the hokiest, cheapest aspects of Mississippi Burning. Kaplan earns his keep in the two most carefully framed and inventively shot sequences in the movie: an eerie, extended crane shot in which the rest of Dallas is slowly learning the lethal fate of JFK (but before Kennedy disciple Lurene has figured it out), and the last shot of the movie, which captures Lurene's flakiness as well as her emotional generosity without totally pulling focus away from Haysbert's climactic reunion with his daughter. But this careful balancing of tones, the sweet and the serious, the kooky and the acute, is a feat the Pfeiffer pulls off much more often than her director does, and much more memorably.

Kaplan earns his keep in the two most carefully framed and inventively shot sequences in the movie: an eerie, extended crane shot in which the rest of Dallas is slowly learning the lethal fate of JFK (but before Kennedy disciple Lurene has figured it out), and the last shot of the movie, which captures Lurene's flakiness as well as her emotional generosity without totally pulling focus away from Haysbert's climactic reunion with his daughter. But this careful balancing of tones, the sweet and the serious, the kooky and the acute, is a feat the Pfeiffer pulls off much more often than her director does, and much more memorably.

After Love Field, Kaplan's career mostly detoured into failed B-movies like the Andie MacDowell western Bad Girls and the bracing but forgettable Madeleine Stowe thriller Unlawful Entry. Lots of other people went on to do better work, often to the explicit discredit of Love Field: Roos wrote sturdier, more adventurous movies, some of which he even directed with real aplomb (tonally, if not visually); Haysbert magnificently semi-romanced another deluded but gorgeously-intentioned white housewife in Far from Heaven; blink-and-you'll-miss-her Beth Grant earned better spotlights for her delicious caricatures of high-strung eccentrics in Donnie Darko and Little Miss Sunshine. As for Pfeiffer, she rode a bus much more expressively in the opening scenes of Frankie and Johnny (still my favorite of her performances) than she does here, and the daring stylization of Catwoman and romantic raptures of Countess Ellen Olenska made Love Field look like a shoestringy, between-commitments type of project. As the 90s wore on, she took a lot more of those movies (To Gillian on Her 37th Birthday, One Fine Day, Up Close & Personal, The Story of Us...), so maybe Love Field, sticking out in odd, unbeloved ways amidst the most exciting and courageous passage in her career, looks unflattering now as a harbinger of future films that wouldn't quite deserve her, or demand enough of her.

After Love Field, Kaplan's career mostly detoured into failed B-movies like the Andie MacDowell western Bad Girls and the bracing but forgettable Madeleine Stowe thriller Unlawful Entry. Lots of other people went on to do better work, often to the explicit discredit of Love Field: Roos wrote sturdier, more adventurous movies, some of which he even directed with real aplomb (tonally, if not visually); Haysbert magnificently semi-romanced another deluded but gorgeously-intentioned white housewife in Far from Heaven; blink-and-you'll-miss-her Beth Grant earned better spotlights for her delicious caricatures of high-strung eccentrics in Donnie Darko and Little Miss Sunshine. As for Pfeiffer, she rode a bus much more expressively in the opening scenes of Frankie and Johnny (still my favorite of her performances) than she does here, and the daring stylization of Catwoman and romantic raptures of Countess Ellen Olenska made Love Field look like a shoestringy, between-commitments type of project. As the 90s wore on, she took a lot more of those movies (To Gillian on Her 37th Birthday, One Fine Day, Up Close & Personal, The Story of Us...), so maybe Love Field, sticking out in odd, unbeloved ways amidst the most exciting and courageous passage in her career, looks unflattering now as a harbinger of future films that wouldn't quite deserve her, or demand enough of her. But hell, you know? It's an admirable and engaging performance, and she did win Best Actress at the Berlin Film Festival. She gets some great moments out of a hot pink carrying-case, a partially memorized license plate, a cantaloupe-colored suit with matching hat, a missed encounter with Jackie O., and a nervous grab at her unfastened sweater as she briskly, hilariously walks diagonally through her final shot. Pfeiffer's Lurene is certainly the equal of agreeable also-rans in other years, like Renée Zellweger in Bridget Jones's Diary or (dare I suggest it?) Annette Bening in Being Julia, and though no sensible voter would have denied the 1992 Best Actress Oscar to Emma Thompson in Howards End, all four of the fellow nominees (to include Sarandon in Lorenzo's Oil, Deneuve in Indochine, and the marvelous Mary McDonnell in Passion Fish) deserve more credit than the media of the moment afforded them. Pfeiffer's Lurene is not an immortal creation, but in fact she's agreeably and appropriately miniature: a kind, sheltered gal who isn't quite as silly as she looks, nor as sober and stately as star-vehicle sometimes require. She's behind glass a little bit, tentatively tapping on the door of a wider world that she doesn't know much about. It's fun to join her for the outset of that journey.

But hell, you know? It's an admirable and engaging performance, and she did win Best Actress at the Berlin Film Festival. She gets some great moments out of a hot pink carrying-case, a partially memorized license plate, a cantaloupe-colored suit with matching hat, a missed encounter with Jackie O., and a nervous grab at her unfastened sweater as she briskly, hilariously walks diagonally through her final shot. Pfeiffer's Lurene is certainly the equal of agreeable also-rans in other years, like Renée Zellweger in Bridget Jones's Diary or (dare I suggest it?) Annette Bening in Being Julia, and though no sensible voter would have denied the 1992 Best Actress Oscar to Emma Thompson in Howards End, all four of the fellow nominees (to include Sarandon in Lorenzo's Oil, Deneuve in Indochine, and the marvelous Mary McDonnell in Passion Fish) deserve more credit than the media of the moment afforded them. Pfeiffer's Lurene is not an immortal creation, but in fact she's agreeably and appropriately miniature: a kind, sheltered gal who isn't quite as silly as she looks, nor as sober and stately as star-vehicle sometimes require. She's behind glass a little bit, tentatively tapping on the door of a wider world that she doesn't know much about. It's fun to join her for the outset of that journey.

Arctic Tale - So where are these so-called environmentalists when Queen Latifah's out here narrating fart-jokes over footage of struggling polar bears? I mean, don't polar bears have some sort of lobbying group that they could put an end to this sort of representation? Give the dudes a little respect, they're totally worthy.

Arctic Tale - So where are these so-called environmentalists when Queen Latifah's out here narrating fart-jokes over footage of struggling polar bears? I mean, don't polar bears have some sort of lobbying group that they could put an end to this sort of representation? Give the dudes a little respect, they're totally worthy. Who's Your Caddy? - I caught some of Ferris Bueller on TV a few weeks ago and lamented to the boyfriend the fall of Jeffrey Jones (who in 2003 plead no contest to, according to IMDb, "one felony count of employing a minor for purposes of taking sexually explicit photos" and "was placed on a sex offender register"), thinking I'd never see him again (only now, looking at IMDb, do I see he was on Deadwood). Then suddenly there he was, in the trailer for this Caddyshack rip-off... and it made me very sad. Jones was a constant presence in Tim Burton's films - most memorably for me as Charles Deetz in Beetlejuice - and he was fantastic in the under-appreciated Ravenous... he's one of those guys who always fills out the screen, making a picture far more interesting, and while I don't think his conviction should keep him from working again, if he's forced into making this sort of dreck... sad.

Who's Your Caddy? - I caught some of Ferris Bueller on TV a few weeks ago and lamented to the boyfriend the fall of Jeffrey Jones (who in 2003 plead no contest to, according to IMDb, "one felony count of employing a minor for purposes of taking sexually explicit photos" and "was placed on a sex offender register"), thinking I'd never see him again (only now, looking at IMDb, do I see he was on Deadwood). Then suddenly there he was, in the trailer for this Caddyshack rip-off... and it made me very sad. Jones was a constant presence in Tim Burton's films - most memorably for me as Charles Deetz in Beetlejuice - and he was fantastic in the under-appreciated Ravenous... he's one of those guys who always fills out the screen, making a picture far more interesting, and while I don't think his conviction should keep him from working again, if he's forced into making this sort of dreck... sad. I Know Who Killed Me - We've all seen the I Know Who Killed My Career mash-up, right? Did anyone else have a clue that this was actually opening this weekend? I had no idea. The last I knew Lohan was talking about taking stripper classes and there were some pictures of her in stripper clothes... and then Lindsay had some, uh, extracurricular troubles... and now suddenly the movie's coming out? I don't know.

I Know Who Killed Me - We've all seen the I Know Who Killed My Career mash-up, right? Did anyone else have a clue that this was actually opening this weekend? I had no idea. The last I knew Lohan was talking about taking stripper classes and there were some pictures of her in stripper clothes... and then Lindsay had some, uh, extracurricular troubles... and now suddenly the movie's coming out? I don't know. (soundtrack) The girl can't help it she was born to please / (She can't help it, the girl can't help it) / And if I go to her on my bended knees / (She can't help it, the girl can't help it)

(soundtrack) The girl can't help it she was born to please / (She can't help it, the girl can't help it) / And if I go to her on my bended knees / (She can't help it, the girl can't help it)

It has to do with the roundest, yellowest, most unexpected of Hotties – Mr. Homer Simpson.

It has to do with the roundest, yellowest, most unexpected of Hotties – Mr. Homer Simpson. So what is it about this bacon-grease-slurping alcoholic that never fails to shine? Is it that we know that deep down beats the heart of one of the most truly decent, loving fathers and husbands ever put onscreen? One that will do anything for his loved ones, if he has to throw himself off a cliff, a waterfall, an airplane, a ski-lift, into a pit of horny pandas… um, I could keep going… point being, he might get distracted by

So what is it about this bacon-grease-slurping alcoholic that never fails to shine? Is it that we know that deep down beats the heart of one of the most truly decent, loving fathers and husbands ever put onscreen? One that will do anything for his loved ones, if he has to throw himself off a cliff, a waterfall, an airplane, a ski-lift, into a pit of horny pandas… um, I could keep going… point being, he might get distracted by  something shiny here and there – and therein taps into a forgotten well of glee in us all, mind you – and to be honest he's usually the one who messes things up to start with, but when it really matters Homer does right. His heart of gold may be coated with a thick layer of lard, but we end up loving the lug anyway. Surely, come this weekend, he'll be winning our hearts anew, and at forty-feet tall too.

something shiny here and there – and therein taps into a forgotten well of glee in us all, mind you – and to be honest he's usually the one who messes things up to start with, but when it really matters Homer does right. His heart of gold may be coated with a thick layer of lard, but we end up loving the lug anyway. Surely, come this weekend, he'll be winning our hearts anew, and at forty-feet tall too. (voiceover) In my posture class, I was particularly struck by one of the students, a boy with a Polish name. From a certain unevenly rounded thickness at the crotch of his blue jeans, it is safe to assume that he is marvelously hung.

(voiceover) In my posture class, I was particularly struck by one of the students, a boy with a Polish name. From a certain unevenly rounded thickness at the crotch of his blue jeans, it is safe to assume that he is marvelously hung.

...it's easier and more appropriate to read The Little Mermaid as a hormonally addled sexual awakening fable. Ariel does writhe around ecstatically in a bikini but the pleasure she's imaging is inchoate. She (and Disney) is just growing up. It's worth noting that this signature song is not initially about a man. She will meet Prince Eric in the next scene and he will give shape to her longing. The song gains its true title "Part of Your World" [italices mine -ed] only in reprise, after Ariel rescues Eric from drowning. She caresses his face and sings it to him, her desire now tangible. To have him, to grow up, she must become human. This becomes her goal but it's also a frightening journey. The moment her wish is granted is telling, played as it is for sheer terror with thunderbolt flashes of light, her fin splitting --legs opening. What has this young girl done?!read the full article

Given that, it probably won't surprise you to hear that I only watch four or five movies a year in a theater - usually without a date.

Given that, it probably won't surprise you to hear that I only watch four or five movies a year in a theater - usually without a date. Nathaniel: I'm glad you said it. I'm too hard on Noni in general here but I am horrified (horrified!) every time I manage to forget to forget that both of her nominations are for period work and she's just not good at it. Her nominations should've come from work like Heathers and Reality Bites instead. No shame in doing soulful comedic contemporary work --well maybe it's shameful to the Academy voters but not to me.

Nathaniel: I'm glad you said it. I'm too hard on Noni in general here but I am horrified (horrified!) every time I manage to forget to forget that both of her nominations are for period work and she's just not good at it. Her nominations should've come from work like Heathers and Reality Bites instead. No shame in doing soulful comedic contemporary work --well maybe it's shameful to the Academy voters but not to me.  Nathaniel: Popcorn or candy?

Nathaniel: Popcorn or candy? I want Edith Head to do my costumes, but Dolores will probably insist on gowns by Adrian. Yul Brynner, of course, will play me; although Ben Kingsley and Vin Diesel will both lobby ardently for the Oscar-bait role. It'll be Rated NC-17 for the leather bar sequences and constant use of foul language, and be called Follow the Fleece.

I want Edith Head to do my costumes, but Dolores will probably insist on gowns by Adrian. Yul Brynner, of course, will play me; although Ben Kingsley and Vin Diesel will both lobby ardently for the Oscar-bait role. It'll be Rated NC-17 for the leather bar sequences and constant use of foul language, and be called Follow the Fleece.

Critical Pets

Critical Pets Muckworld finds INLAND EMPIRE to be even more of a shapeshifting revelation on DVD

Muckworld finds INLAND EMPIRE to be even more of a shapeshifting revelation on DVD ed

ed

Here are my favorite pieces from 2007...

Here are my favorite pieces from 2007...

"I love what you've done with the place Dorrie, but maybe we could cheer up the rest of Hogwarts, too!"

"I love what you've done with the place Dorrie, but maybe we could cheer up the rest of Hogwarts, too!"

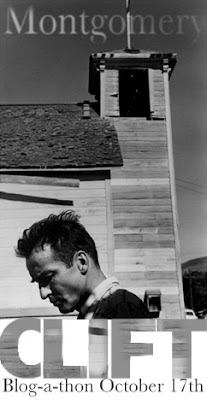

Blog-a-thon Announcement

Blog-a-thon AnnouncementThe Search, Red River, The Heiress, The Big Lift, A Place in the Sun, I Confess, Indiscretion of an American Housewife, From Here to Eternity, Raintree Country, Lonelyhearts, The Young Lions, Suddenly Last Summer, Wild River, The Misfits, Judgment at Nuremberg, Freud, The DefectorMany of those are classics...seriously, what a filmography! Now would be a good time to screen a couple. Other topics of interested: queer Hollywood in the 50s, Oscar battles, and Monty's famous Hollywood friendships with Monroe, Dean Martin, and of course Liz Taylor (his most frequent co-star). The classic film lovers should come out in force for this one and I hope that younger bloggers will take the time to discover him. Monty has detractors too (you know who you are) but anyone is welcome to participate.

Conrad Jarrett: If you’re a friend of Doctor Crawford you’re probably all right but I’ll be straight with you: I don’t like this already.Retrospective film history has turned people against Ordinary People due to the defeat of Raging Bull at the Oscars. Unfortunately the shadow side of revisionist Oscar history is this: good movies get penalized through no fault of their own. The sadness in Timothy Hutton's eyes here...it just rips the heart up.

Dr. Berger: As long as you're straight.

Conrad: What do you know about me --have you talked to Crawford?

Dr. Berger: Yes, he called me on the phone. He told me your name and he told me to look for you. He said you had a brother who died…

What are you doing this weekend?

What are you doing this weekend? I'll leave you with the following batch of pics. First is Tony Stark testing his Iron Man gear which Screen Rant was pretty excited about. Then we have new posters for Darjeeling Limited and No Country For Old Men plus Tom Cruise in Valkyrie, Bryan Singer's next project.

I'll leave you with the following batch of pics. First is Tony Stark testing his Iron Man gear which Screen Rant was pretty excited about. Then we have new posters for Darjeeling Limited and No Country For Old Men plus Tom Cruise in Valkyrie, Bryan Singer's next project.